Humpback dolphin

| Humpback dolphin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Humpback dolphins surfacing for air | |

| |

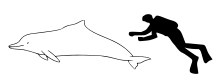

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Delphinidae |

| Subfamily: | Delphininae |

| Genus: | Sousa Gray, 1866 |

| Type species | |

| Steno lentiginosus [1] Gray, 1866

| |

| Species | |

| |

| |

| Range of each species | |

Humpback dolphins are members of the genus Sousa. These dolphins are characterized by the conspicuous humps and elongated dorsal fins found on the backs of adults of the species. Humpback dolphins inhabit shallow nearshore waters along coastlines across Australia, Africa, and Asia. Their preference for these habitats exposes them to various human activities such as fisheries entanglement, boat traffic, pollution, and habitat loss. Despite these risks, their nearshore presence facilitates easy observation from land.

There are four recognized species: the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis), Indian Ocean humpback dolphin (S. plumbea), Atlantic humpback dolphin (S. teuszii), and Australian humpback dolphin (S. sahulensis).

Although generally shy and less active compared to bottlenose dolphins, they are occasionally featured in dolphin watching tours, particularly in locations like Hong Kong and the Musandam Peninsula of Oman.

Description

[edit]The humpback dolphin is a coastal species found from Africa and India south to Australia, with variations in different regions. It has a distinctive hump in front of its dorsal fin and a keel on its belly. The dorsal fin is somewhat curved. Its pectoral fins are relatively small, and the tail flukes have a noticeable notch in the middle. Each side of its jaw has 30 to 34 small, cone-shaped teeth.

They feature a long rostrum, which constitutes 6.3–10.1% of their body length.[2] Their bodies are robust, tapering towards the rear, with distinct keels on both the dorsal and ventral sides of the caudal peduncle across all age groups.[3]

Neonatal lengths in South African waters range from 97 to 108 cm, with maximum recorded lengths up to 2.8 m.[2] Among Sousa species, Sousa plumbea is the largest, with reported lengths exceeding 3.0 m in the Arabian and Indian regions,[4] although some dispute these reports.[5]

Southern African dolphin calves have a lighter coloration compared to adults.[2] Calves exhibit pale grey coloration on their flanks with a whiter ventral side, transitioning to darker grey on their back and upper flukes. A diffuse grey stripe runs from the eye towards the flipper, while the dorsal and ventral keels of the caudal peduncle appear off-white. This color pattern persists into adulthood but darkens over time, with some of the largest adults showing white areas on the dorsal fin and hump.[3] Many individuals exhibit prominent scars on their dorsal fin and back, believed to result from unsuccessful shark attacks.[6]

The species is characterized by smaller organ weights, indicating it is a shallow-diving, relatively slow-moving coastal delphinid compared to species like the Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) and long-beaked common dolphins (Delphinus capensis).[7] Research has been most extensive in South African populations in Algoa Bay and Richards Bay, although these may not fully represent other populations in the subregion.[3]

Diet

[edit]Studies on the diet of Humpback dolphins have mostly been restricted to individuals either stranded on shore or caught in shark nets. They feed almost exclusively on fish, although they have been known to occasionally prey on cephalopods as well.[8] These dolphins mainly eat fish that live near reefs, in estuaries, and on the ocean floor.[9][10] A study from 1983 examining the stomachs of 17 humpback dolphins found that glassnosed anchovy (Thryssa vitrirostris) was the most common prey, followed by ribbon fish (Trichiurus lepturus), olive grunter (Pomadasys olivaceum), and longtooth kob (Otolithes ruber).[11] A study of Humpback dolphins stranded in Hong Kong from 1994-2000 had similar results, with the addition of cutlassfishes, sardines, mullets, and catfish. The presence of catfish as prey is notable due to their venomous spines, which have been implicated in the deaths of dolphins elsewhere.[12] A more recent study in 2013 analyzing the stomach contents of 22 humpback dolphins (13 males, 9 females) caught in shark nets in the KwaZulu-Natal Coastline identified 59 different prey species. The main prey species were similar to those found earlier, with the addition of the bearded croaker (Johnius amblycephalus).[13]

Humpback dolphins employ diverse feeding strategies, such as beaching themselves partially to chase after fish. Additionally, in certain areas, these dolphins are observed trailing fishing trawlers to exploit discarded or escaped fish as a feeding opportunity.[14] Though this behavior may conserve energy and supplement their diet, it also exposes them to risk of entanglement in nets. Two dolphins suspected of being caught in trawler nets (SC96-31/05 and SC97-31/5B) were found with undigested fish and nearly full stomachs, including significant quantities of prey species like Johnius and Collichthys lucida, commonly caught by trawlers.[15]

Taxonomy

[edit]- Genus Sousa:

- S. chinensis (Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin)

- S. plumbea (Indian Ocean humpback dolphin)

- S. teuszii (Atlantic humpback dolphin)

- S. sahulensis (Australian humpback dolphin)

By the mid-2000s, most authorities[16][17][18] accepted just two species—the Atlantic and the Indo-Pacific. However, in his widely used systematic account,[19] Rice identified three species, viewing the Indo-Pacific as two species named simply the Indian and Pacific. The dividing line between the two (sub)species is taken to be Sumatra, one of the Indonesian islands; however, intermixing is thought to be inevitable.

Further, Australian cetologist Graham Ross writes "However, recent morphological studies, somewhat supported equivocally by genetic analyses, indicate that there is a single, variable species for which the name S. chinensis has priority".[10]

Humpback dolphins found in Chinese waters are locally known as Chinese white dolphins. See that article for specific issues relating to that subspecies which corresponds to the Pacific humpback dolphin in Rice's classification.

In late 2013, researchers from the Wildlife Conservation Society and the American Natural History museum proposed classification of the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin into three species based on morphological and genetic analysis.[20] Their research indicates that at least four species make up the genus Sousa: the Atlantic humpback dolphin (S. teuszii), two species of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (S. plumbea and S. chinesis), and a fourth, new species of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin found off northern Australia, a distinction with potential to guide conservation efforts for the species.[21][22]

Conservation

[edit]S. teuszii is listed on Appendix I[23][24] and Appendix II (along with S. chinensis)[23][24] of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). It is listed on Appendix I[23][24] as this species has been categorized as being in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant proportion of its range and CMS Parties strive towards strictly protecting these animals, conserving or restoring the places where they live, mitigating obstacles to migration and controlling other factors that might endanger them. It is listed on Appendix II[23][24] as it has an unfavourable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organised by tailored agreements. [25]

In addition, the Atlantic humpback dolphin is covered by the Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Conservation of the Manatee and Small Cetaceans of Western Africa and Macaronesia.[26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M., eds. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c Ridgway, Sam H. (1994). Handbook of Marine Mammals 5: The First Book of Dolphins (1st ed.). Academic Press. pp. 23–42. ISBN 978-0125885058.

- ^ a b c Best, Peter B. (19 January 2009). Whales and Dolphins of the Southern African Subregion (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 338. ISBN 978-0521897105.

- ^ Parra, Guido J.; Ross, Graham J. B. (1 January 2009), "Humpback Dolphins: S. chinensis and S. teuszii", in Perrin, William F.; Würsig, Bernd; Thewissen, J. G. M. (eds.), Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (Second Edition), London: Academic Press, pp. 576–582, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-373553-9.00134-6, ISBN 978-0-12-373553-9, retrieved 7 July 2024

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas A.; Rosenbaum, Howard C. (1 August 2014). "Taxonomic revision of the humpback dolphins ( Sousa spp.), and description of a new species from Australia". Marine Mammal Science. 30 (4): 1494–1541. Bibcode:2014MMamS..30.1494J. doi:10.1111/mms.12152. ISSN 0824-0469.

- ^ Nicholls, Caitlin R.; Peters, Katharina J.; Cagnazzi, Daniele; Hanf, Daniella; Parra, Guido J. (May 2023). "Incidence of shark-inflicted bite injuries on Australian snubfin ( Orcaella heinsohni ) and Australian humpback ( Sousa sahulensis ) dolphins in coastal waters off east Queensland, Australia". Ecology and Evolution. 13 (5): e10026. Bibcode:2023EcoEv..1310026N. doi:10.1002/ece3.10026. ISSN 2045-7758. PMC 10156446. PMID 37153022.

- ^ Plon, S.; Albrecht, K. H.; Cliff, G.; Froneman, P. W. (2012). "Organ weights of three dolphin species (Sousa chinensis, Tursiops aduncus and Delphinus capensis) from South Africa: implications for ecological adaptation?". J. Cetacean Res. Manage. 12 (2): 265–276. doi:10.47536/jcrm.v12i2.584. ISSN 2312-2706.

- ^ Barros, Nélio B.; Jefferson, Thomas A.; Parsons, E.C.M. (1 January 2004). "Feeding Habits of Indo-Pacific Humpback Dolphins (Sousa chinensis) Stranded in Hong Kong". Aquatic Mammals. 30 (1): 179–188. doi:10.1578/AM.30.1.2004.179.

- ^ Parra, Guido J.; Ross, Graham J.B. (2009), "Humpback Dolphins", Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, Elsevier, pp. 576–582, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-373553-9.00134-6, ISBN 978-0-12-373553-9, retrieved 7 July 2024

- ^ a b Humpback Dolphins Graham J. B. Ross pps 585-589 in Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (1998) ISBN 0-12-551340-2

- ^ Cockcroft, V. G. & Ross, G. J. B. (1983). Feeding of three inshore delphinid species in Natal waters. Fifth national oceanographic symposium, Grahamstown, January 1983. Advance Abstr. Symp. C.S.l.R. S288: G6.

- ^ Barros, Nélio B.; Jefferson, Thomas A.; Parsons, E.C.M. (1 January 2004). "Feeding Habits of Indo-Pacific Humpback Dolphins (Sousa chinensis) Stranded in Hong Kong". Aquatic Mammals. 30 (1): 179–188. doi:10.1578/AM.30.1.2004.179.

- ^ Atkins, Shanan; Cliff, Geremy; Pillay, Neville (March 2013). "Humpback dolphin bycatch in the shark nets in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa". Biological Conservation. 159: 442–449. Bibcode:2013BCons.159..442A. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2012.10.007.

- ^ "Humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis, S. plumbea, S. teuszii, S. sahulensis)". International Whaling Commission. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Parsons, E. C. M.; Jefferson, T. A. (April 2000). "Post-Mortem Investigations on Stranded Dolphins and Porpoises from Hong Kong Waters". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 36 (2): 342–356. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-36.2.342. ISSN 0090-3558. PMID 10813617.

- ^ National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World (2002) ISBN 0-375-41141-0

- ^ Cetacean Societies: Field Studies of Whales and Dolphins Mann, Connor, Tyack and Whitehead (2000) ISBN 0-226-50340-2

- ^ Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises Mark Carwardine (1995) ISBN 0-7513-2781-6

- ^ Land Mammals of the World. Systematics and Distribution, Dale W. Rice (2000). Published by the Society of Marine Mammalogy as Special Publication No. 4

- ^ Mendez, M.; Jefferson, T. J.; Kolokotronis, S. O.; Krützen, M.; Parra, G. J.; Collins, T.; Minton, G.; Baldwin, R.; Berggren, P.; Särnblad, A.; Amir, O. A.; Peddemors, V. M.; Karczmarski, L.; Guissamulo, A.; Smith, B.; Sutaria, D.; Amato, G.; Rosenbaum, H. C. (2013). "Integrating multiple lines of evidence to better understand the evolutionary divergence of humpback dolphins along their entire distribution range: A new dolphin species in Australian waters?". Molecular Ecology. 22 (23): 5936–5948. Bibcode:2013MolEc..22.5936M. doi:10.1111/mec.12535. PMID 24268046. S2CID 9467569.

- ^ "WCS Newsroom".

- ^ "Atlantic Humpback Dolphin (Sousa teuszii) - Dolphin Facts and Information". www.dolphins-world.com. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Appendix I and Appendix II Archived 11 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine" of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). As amended by the Conference of the Parties in 1985, 1988, 1991, 1994, 1997, 1999, 2002, 2005 and 2008. Effective: 5 March 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Species | CMS". www.cms.int. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Convention on Migratory Species page on the Atlantic humpback dolphin". Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- ^ Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Conservation of the Manatee and Small Cetaceans of Western Africa and Macaronesia